Prefix Sum on WebGPU: from Hillis–Steele, Blelloch, to Subgroups

Writing some WebGPU compute shaders that can scan faster than the CPU

In this article I implement prefix sum using WebGPU compute shaders, aiming to beat a straightforward CPU sequential prefix sum. The implementation is written in Rust with wgpu.

For everything except the subgroup part, I mainly followed the classic explanation in GPU Gems 3, Chapter 39.

Full source code is here.

You can find the Japanese version of this article from below.

What is a prefix sum?

Given an array , a prefix sum array is defined as . In other words, contains the sum of for inclusive scan or for exclusive scan. Prefix sums show up everywhere, i.e. radix sort, quadtrees, and a bunch of other “build a structure from counts/offsets” workloads.

A naive in-place CPU implementation looks like the following pseudocode.

function inclusiveScan(A[0..n-1])

for i:= 1,..,n-1 do

A[i] := A[i-1] + A[i]

end for

end functionThe problem for GPU implementation is obvious, each element depends on the previous result, so the naive form doesn’t parallelize. That’s why we need scan algorithms designed for parallel hardware.

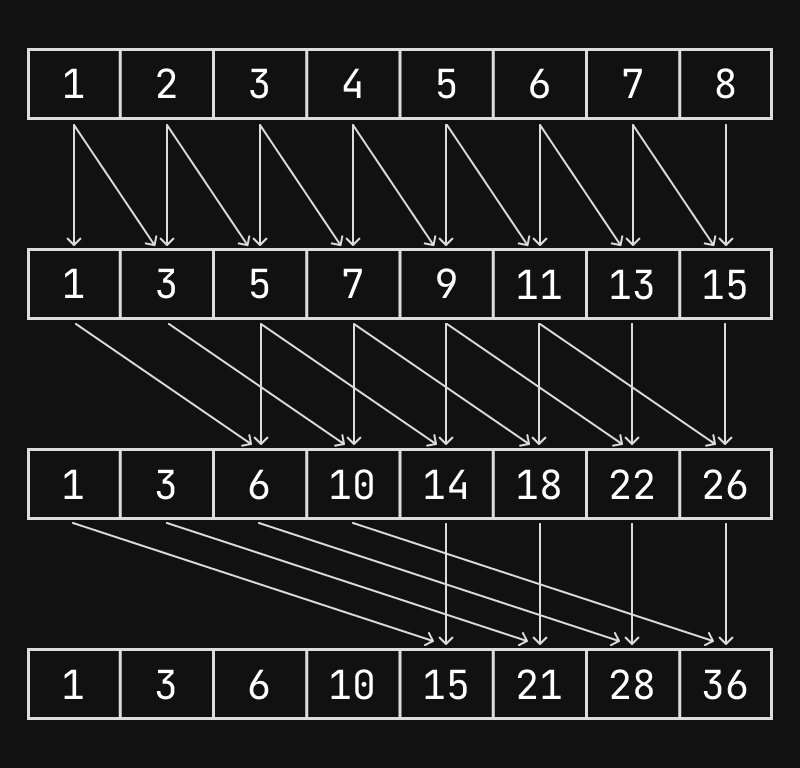

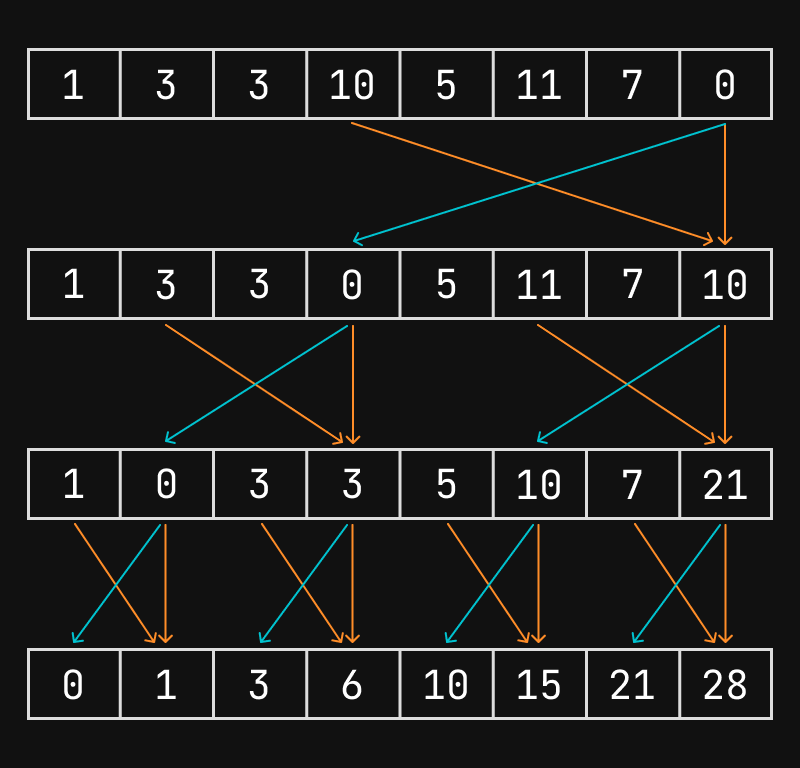

Hillis–Steele scan

Hillis–Steele is an iterative algorithm where the dependency distance doubles each step. If you draw a binary-tree-like reduction that computes from leaves , you’ll notice that at each height you only depend on two values, which is a good start for parallel execution.

Implementation

Hillis–Steele is typically described as “in-place”, but if you try to do it with a single buffer on a GPU you’ll quickly run into read-after-write hazards, that mean you might read values that were already updated in the same step. One solution for the problem is using double buffering.

// hillis_steele_scan.rs

let byte_len = (n * size_of::<u32>()) as u64;

let data0 = device.create_buffer(&wgpu::BufferDescriptor {

label: Some("data0"),

size: byte_len,

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::STORAGE

| wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_DST

| wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_SRC,

mapped_at_creation: false,

});

let data1 = device.create_buffer(&wgpu::BufferDescriptor {

label: Some("data1"),

size: byte_len,

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::STORAGE

| wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_DST

| wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_SRC,

mapped_at_creation: false,

});Next, we need to pass the current step size into the shader: . WebGPU provides uniform buffers for this kind of small “constant-ish” data.

You could update the same uniform buffer every iteration, dispatch and submit at a time, and repeat… but submit is not free (validation, scheduling, driver work, etc.). Instead, I precompute all steps into a single uniform buffer and use dynamic offsets so one submit can dispatch every step.

// hillis_steele_scan.rs

let align = device.limits().min_uniform_buffer_offset_alignment as usize;

let uni_size = size_of::<Uniforms>();

let stride = align_up(uni_size, align);

let uniform_stride = stride as u32;

// Pack uniforms with required stride

let mut blob = vec![0u8; stride * (max_steps as usize)];

for i in 0..max_steps {

let u = Uniforms {

step: 1u32 << i,

_pad: [0; 3],

};

let bytes = bytemuck::bytes_of(&u);

let offset = (i as usize) * stride;

blob[offset..offset + bytes.len()].copy_from_slice(bytes);

}

let uniform = device.create_buffer_init(&wgpu::util::BufferInitDescriptor {

label: Some("uniform"),

contents: &blob,

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::UNIFORM | wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_DST,

});To enable dynamic offsets, the bind group layout needs has_dynamic_offset: true for the uniform binding.

// hillis_steele_scan.rs

let bind_group_layout = device.create_bind_group_layout(&wgpu::BindGroupLayoutDescriptor {

label: Some("prefix-sum bgl"),

entries: &[

// src

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutEntry {

binding: 0,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStages::COMPUTE,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::Buffer {

ty: wgpu::BufferBindingType::Storage { read_only: true },

has_dynamic_offset: false,

min_binding_size: None,

},

count: None,

},

// dst

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutEntry {

binding: 1,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStages::COMPUTE,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::Buffer {

ty: wgpu::BufferBindingType::Storage { read_only: false },

has_dynamic_offset: false,

min_binding_size: None,

},

count: None,

},

// uniforms (dynamic offset!)

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutEntry {

binding: 2,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStages::COMPUTE,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::Buffer {

ty: wgpu::BufferBindingType::Uniform,

has_dynamic_offset: true,

min_binding_size: NonZeroU64::new(size_of::<Uniforms>() as u64),

},

count: None,

},

],

});

let pipeline_layout = device.create_pipeline_layout(&wgpu::PipelineLayoutDescriptor {

label: Some("prefix-sum pipeline layout"),

bind_group_layouts: &[&bind_group_layout],

immediate_size: 0,

});The WGSL shader itself is fairly compact.

// hillis_steele_scan.wgsl

struct Uniforms {

step: u32,

};

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read> src: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> dst: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(2) var<uniform> uni: Uniforms;

@compute

@workgroup_size(64)

fn main(

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) nwg: vec3<u32>,

) {

let total = arrayLength(&src);

let width = nwg.x * 64u;

let i = gid.x + gid.y * width;

if (i >= total) {

return;

}

if (i < uni.step) {

dst[i] = src[i];

} else {

dst[i] = src[i] + src[i - uni.step];

}

}Then we just dispatch all steps in one compute pass.

// hillis_steele_scan.rs

pub fn run_prefix_scan(&self) {

const WG_SIZE: u32 = 64;

let workgroups_needed = self.n.div_ceil(WG_SIZE as usize) as u32;

let max_dim = self.device.limits().max_compute_workgroups_per_dimension;

let x = workgroups_needed.min(max_dim);

let y = (workgroups_needed + x - 1) / x;

let mut encoder = self.device.create_command_encoder(&Default::default());

{

let mut pass = encoder.begin_compute_pass(&Default::default());

pass.set_pipeline(&self.pipeline);

for i in 0..self.max_steps {

let offset_bytes = i * self.uniform_stride;

let bg = if i % 2 == 0 { &self.bind_group_0 } else { &self.bind_group_1 };

pass.set_bind_group(0, bg, &[offset_bytes]);

pass.dispatch_workgroups(x, y, 1);

}

}

self.queue.submit([encoder.finish()]);

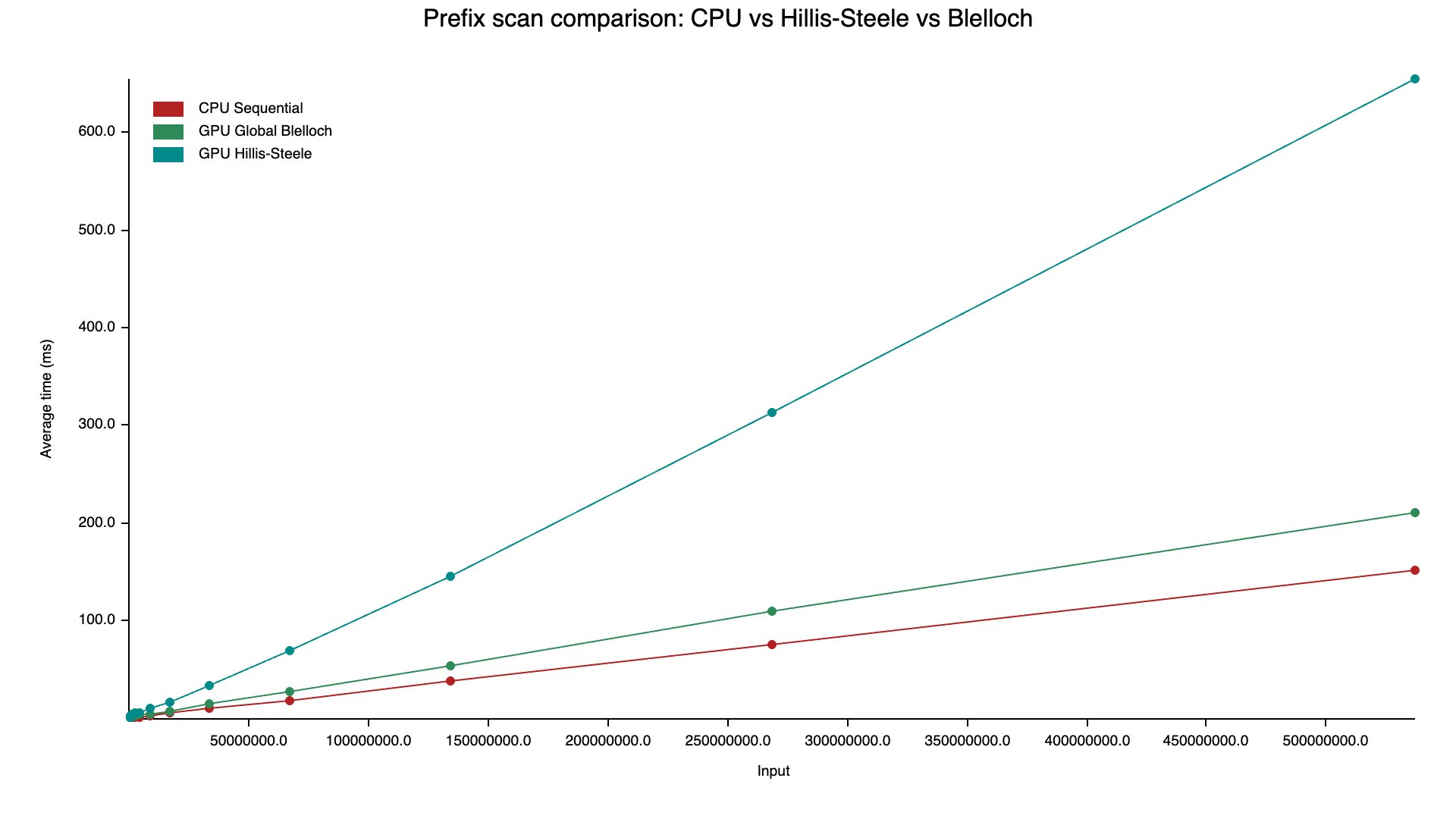

}Benchmark

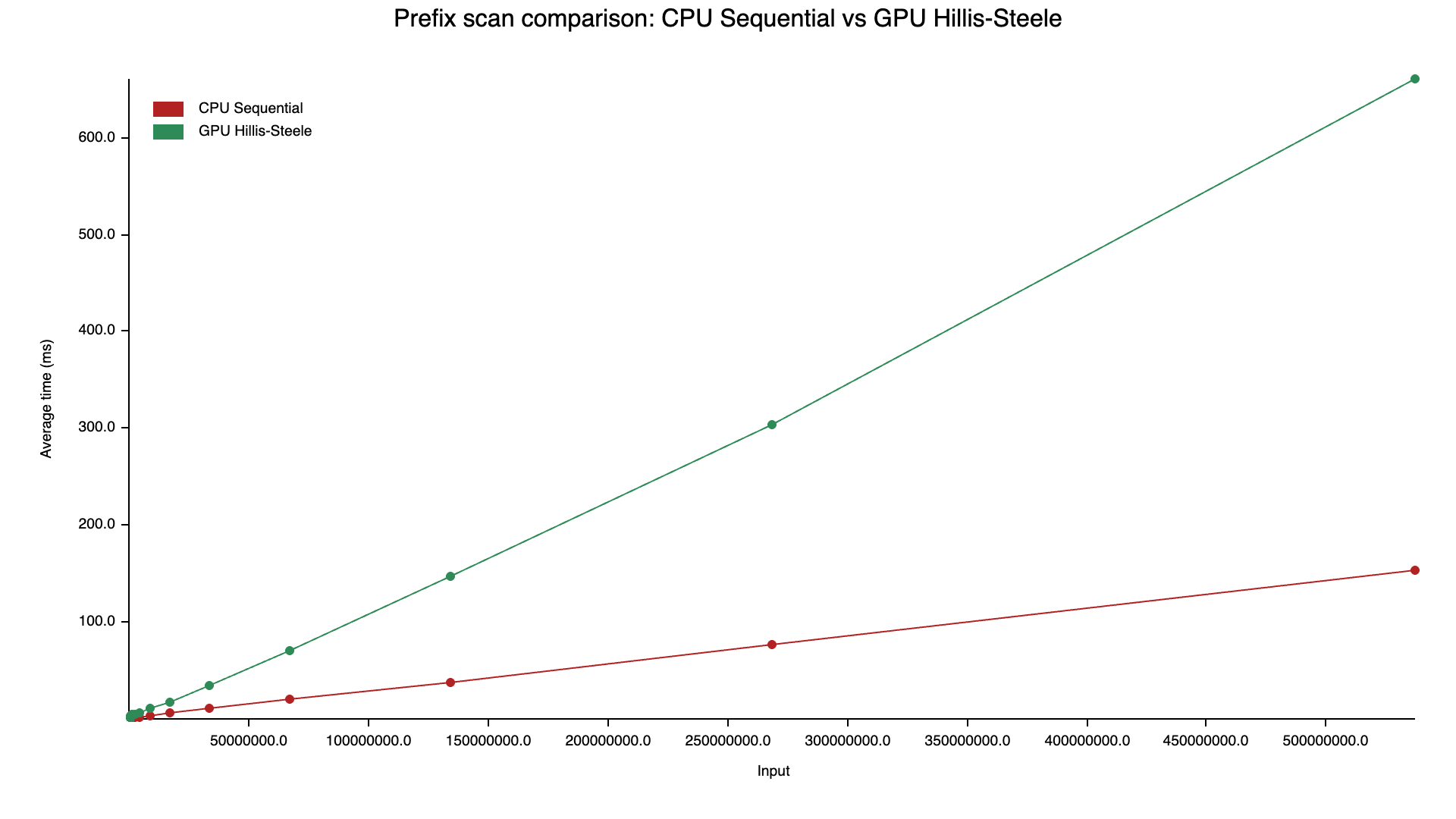

Test machine: M4 Pro Mac mini (24GB). I used Criterion for benchmarking.

Ideally timestamp-query should be the best way for this benchmark, but on Metal I couldn’t get it to work for some reasons, so I measure from submit until the device becomes usable again. This includes a polling overhead (on my machine 500µs to 1ms), but that’s good enough if we compare at large .

…and way slower than sequential scan on CPU.

Hillis–Steele has an ideal parallel time of , so it sounds like it could be faster than sequential scan. But in practice it’s bottlenecked by memory bandwidth and work inefficiency.

Let’s do a rough bandwidth-based estimate. On M4 Pro, the unified memory bandwidth is advertised as 273 GB/s.

If and we store u32, the array size is bytes = bytes 400 MB. Hillis–Steele needs steps. With double buffering, each step touches the whole array with one read and one write → about 2× array traffic per step.

- Total transfers ≈

- Ideal bandwidth time ≈ s ≈ 79.1 ms

In my measurement at , it took 104.36 ms, which is consistent with “bandwidth dominates, plus overheads”.

Also, if you execute Hillis–Steele on a single thread, the total work is , which is not optimal compared to algorithms.

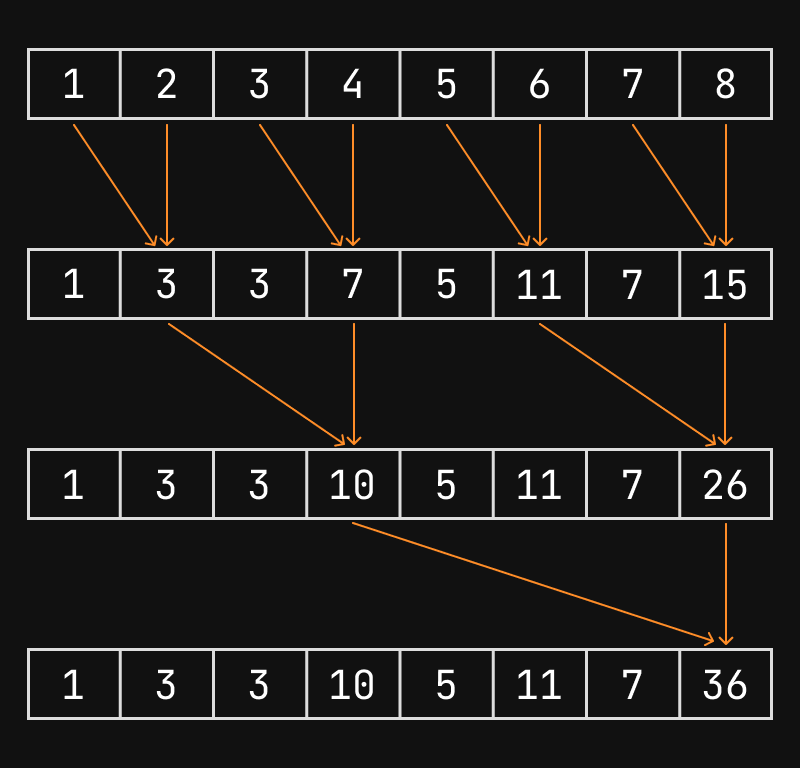

Blelloch scan

Blelloch scan fixes the two big Hillis–Steele issues,

- Work:

- Parallel time: (where is the number of threads)

Blelloch has two phases, up-sweep for building partial sums in a tree-reduction pattern, then down-sweep for converting the tree sums into a prefix sum. The bottom pictures demonstrates exclusive scan with Blelloch’s algorithm.

Before the down-sweep, you set the last element to 0. In down-sweep, if we call the previous index and the current index , the core update is .

It looks like wizardry, but if you trace one element backward through the tree it really does become the right prefix sum.

Implementation

The overall structure is similar to Hillis–Steele, but no double buffer is needed anymore. Here are the WGSL kernels of the up-sweep and the down-sweep steps.

// global_blelloch_scan_up_sweep.wgsl

struct Uniform {

step: u32, // power of 2

};

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> data: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<uniform> uni: Uniform;

@compute

@workgroup_size(64)

fn main(

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) nwg: vec3<u32>,

) {

let n = arrayLength(&data);

let step = uni.step;

let half = step >> 1u;

let width = nwg.x * 64u;

let plane = width * nwg.y;

let t = gid.x + gid.y * width + gid.z * plane;

let active_idx = n / step;

if (t >= active_idx) { return; }

let i = (step - 1u) + t * step;

data[i] += data[i - half];

}// global_blelloch_scan_down_sweep.wgsl

struct Uniform {

step: u32, // power of 2

};

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> data: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<uniform> uni: Uniform;

@compute

@workgroup_size(64)

fn main(

@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) nwg: vec3<u32>,

) {

let n = arrayLength(&data);

let step = uni.step;

let half = step >> 1u;

let width = nwg.x * 64u;

let plane = width * nwg.y;

let t = gid.x + gid.y * width + gid.z * plane;

let active_idx = n / step;

if (t >= active_idx) { return; }

let i = (step - 1u) + t * step;

let prev = i - half;

let left = data[i];

data[i] = data[i] + data[prev];

data[prev] = left;

}Benchmark

Much better than Hillis–Steele, but still not ideal. Even though we reduced work, this implementation still hits global memory a lot (roughly reads/writes on my implementation I guess), so there’s room to improve.

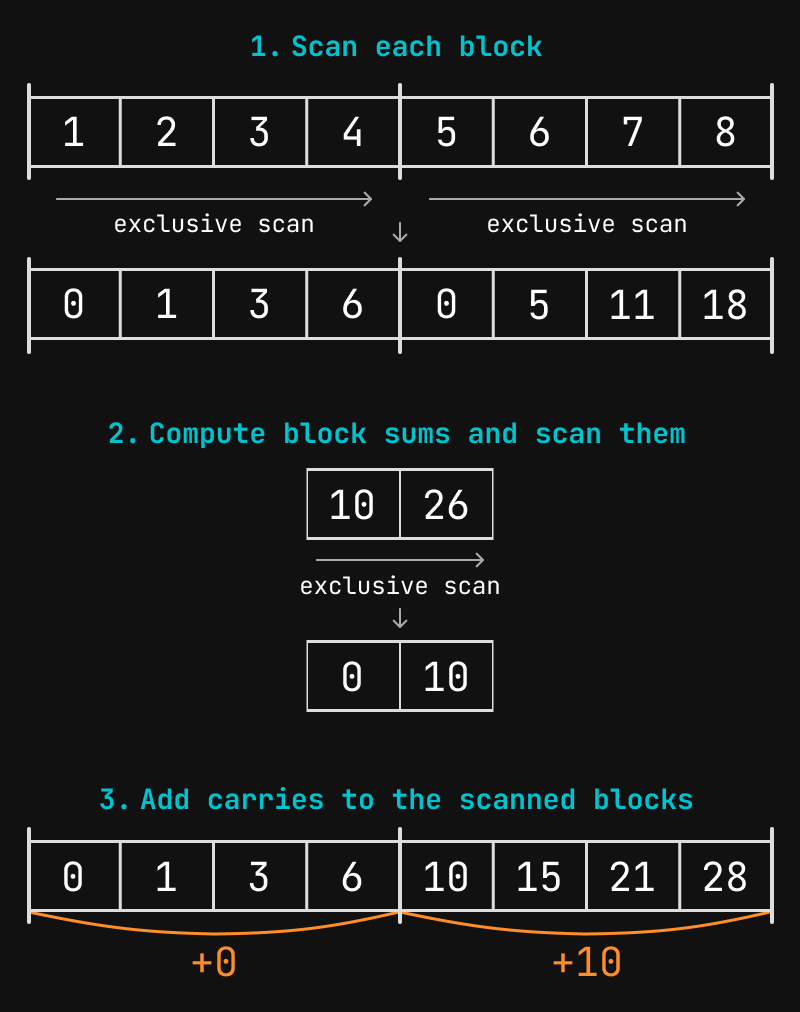

Blocked Blelloch scan

The next optimization is using workgroup (shared) memory. In WGSL that’s var<workgroup>.

We pick the block size to match the workgroup size. Then,

- Compute an exclusive scan inside each block

- Write each block’s total sum into a separate block sum array

- Scan block sum array to get offsets

- Add those offsets back into the already-scanned blocks (“carry add”)

Scanning block sum array is itself a prefix sum problem, so we apply the same logic recursively until the block sum array fits into a single block.

Implementation

The core idea is still Blelloch’s, but we use workgroup memory to reduce the amount of global memory access. This enables us to move the up-sweep and down-sweep loops into a single shader, as we can use a workgroup barrier to synchronise the work within a workgroup. This greatly simplifies the implementation of recursive calls to the scan.

// blelloch_block_scan.wgsl

const WG_SIZE: u32 = 64u;

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> global_data: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> block_sum: array<u32>;

var<workgroup> local_data: array<u32, 64u>;

fn linearize_workgroup_id(wid: vec3<u32>, num_wg: vec3<u32>) -> u32 {

return wid.x + wid.y * num_wg.x + wid.z * (num_wg.x * num_wg.y);

}

fn get_indices(lid: vec3<u32>, wid: vec3<u32>, num_wg: vec3<u32>) -> array<u32, 2> {

let local_idx = lid.x;

let wg_linear = linearize_workgroup_id(wid, num_wg);

let block_base = wg_linear * WG_SIZE;

let global_idx = block_base + local_idx;

return array<u32, 2>(local_idx, global_idx);

}

fn copy_global_data_to_local(n: u32, local_idx: u32, global_idx: u32) {

var global_val = 0u;

if (global_idx < n) { global_val = global_data[global_idx]; }

local_data[local_idx] = global_val;

workgroupBarrier();

}

fn up_sweep(local_idx: u32) {

var step = 2u;

while (step <= WG_SIZE) {

let num_targets = WG_SIZE / step;

if (local_idx < num_targets) {

let target_idx = (local_idx + 1u) * step - 1u;

local_data[target_idx] += local_data[target_idx - (step >> 1u)];

}

workgroupBarrier();

step = step << 1u;

}

}

fn down_sweep(local_idx: u32) {

var step = WG_SIZE;

while (step >= 2u) {

let num_targets = WG_SIZE / step;

if (local_idx < num_targets) {

let target_idx = (local_idx + 1u) * step - 1u;

let prev_idx = target_idx - (step >> 1u);

let prev_val = local_data[prev_idx];

local_data[prev_idx] = local_data[target_idx];

local_data[target_idx] += prev_val;

}

workgroupBarrier();

step = step >> 1u;

}

}

@compute @workgroup_size(WG_SIZE)

fn block_scan_write_sum(

@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) num_wg: vec3<u32>

) {

let n = arrayLength(&global_data);

let indices = get_indices(lid, wid, num_wg);

let local_idx = indices[0];

let global_idx = indices[1];

copy_global_data_to_local(n, local_idx, global_idx);

up_sweep(local_idx);

// write block sum, then set last element to 0

let wg_linear = linearize_workgroup_id(wid, num_wg);

let n_blocks = arrayLength(&block_sum);

if (local_idx == 0u) {

if (wg_linear < n_blocks) {

block_sum[wg_linear] = local_data[WG_SIZE - 1u];

}

local_data[WG_SIZE - 1u] = 0u;

}

workgroupBarrier();

down_sweep(local_idx);

if (global_idx < n) {

global_data[global_idx] = local_data[local_idx];

}

}Carry add is just reading the block offset and adding it to each element in the block.

// blelloch_add_carry.wgsl

const WG_SIZE: u32 = 64u;

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read_write> global_data: array<u32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read_write> block_sum: array<u32>;

fn linearize_workgroup_id(wid: vec3<u32>, num_wg: vec3<u32>) -> u32 {

return wid.x + wid.y * num_wg.x + wid.z * (num_wg.x * num_wg.y);

}

@compute @workgroup_size(WG_SIZE)

fn add_carry(

@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) num_wg: vec3<u32>,

) {

let n_data = arrayLength(&global_data);

let n_blocks = arrayLength(&block_sum);

let wg_linear = linearize_workgroup_id(wid, num_wg);

if (wg_linear >= n_blocks) { return; }

let global_idx = wg_linear * WG_SIZE + lid.x;

if (global_idx >= n_data) { return; }

let carry = block_sum[wg_linear];

global_data[global_idx] += carry;

}On the CPU side, we build the intermediate buffers and bind groups for each recursive level”, then dispatch them in sequence.

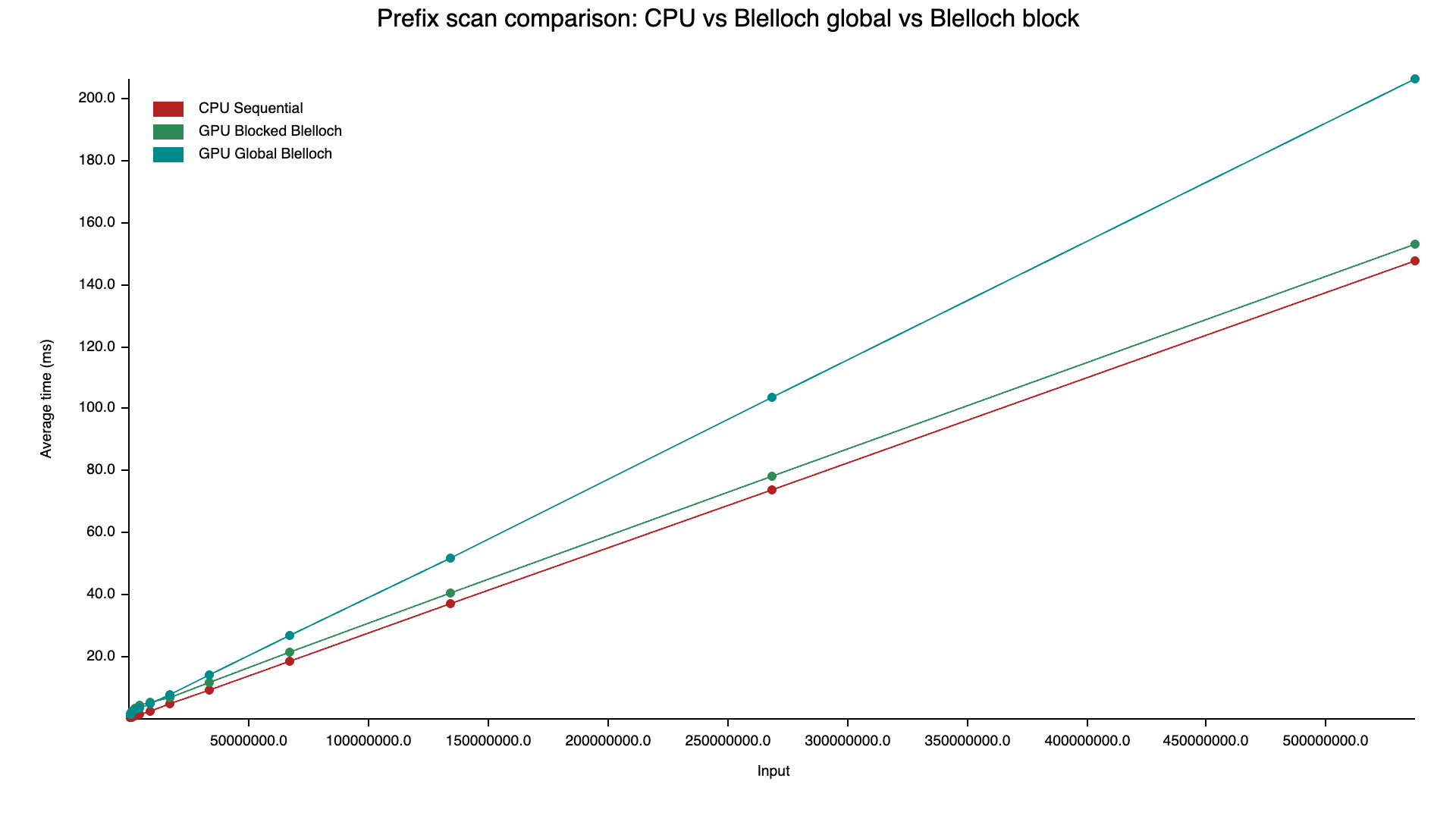

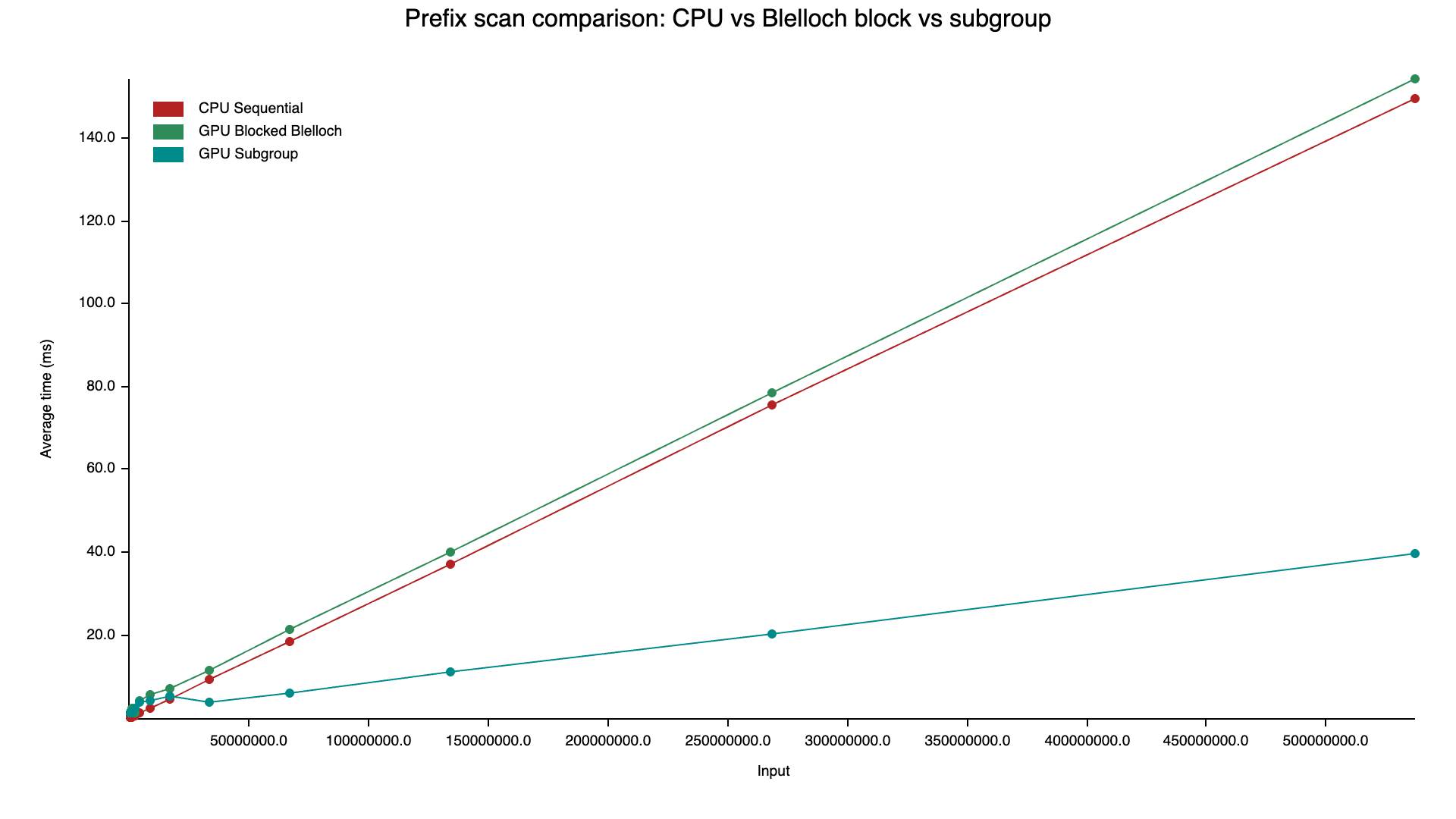

Benchmark

This was slightly faster than the global-memory version, and it got roughly comparable to the CPU.

I also tried the “process 2 or 4 elements per thread” optimization mentioned in GPU Gems 3, but on my setup it actually got slower. I tested workgroup sizes from 32 to 256, and 64 was consistently best. My guess is that with more barriers, larger workgroups (or heavier per-thread work) create more imbalance and longer waits at the barriers, but this part is speculation.

Anyway, even with blocked Blelloch scan, it wasn’t clearly beating the CPU.

Scan by subgroups

WebGPU has a feature called subgroups. Subgroups map to hardware concepts like warp or simdgroups, and provide fast cross-lane communication.

Implementation

WGSL provides subgroupExclusiveAdd, which is literally an exclusive scan within a subgroup. This is what we wanted! This also fits the blocked scan approach pretty well, we just need to replace the scanning part with the new method.

Subgroup sizes vary by backend, but are often around 32 or 64, most probably smaller than a workgroup. So we still need a “subgroup sums → scan → add carry” step, but inside each workgroup.

// subgroup_block_scan.wgsl

@compute @workgroup_size(WG_SIZE)

fn block_scan_write_sum(

@builtin(local_invocation_id) lid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(workgroup_id) wid: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(num_workgroups) num_wg: vec3<u32>,

@builtin(subgroup_size) sg_size: u32,

@builtin(subgroup_invocation_id) sg_lane: u32,

@builtin(subgroup_id) sg_id: u32,

) {

let n = arrayLength(&global_data);

let wg_linear = linearize_workgroup_id(wid, num_wg);

let global_idx = wg_linear * WG_SIZE + lid.x;

let in_range = global_idx < n;

var v = 0u;

if (in_range) {

v = global_data[global_idx];

}

// exclusive scan within the subgroup

let sg_prefix = subgroupExclusiveAdd(v);

// subgroup-wide sum (same value for all lanes in the subgroup)

let sg_sum = subgroupAdd(v);

// write each subgroup sum to workgroup memory

if (sg_lane == 0u) {

local_data[sg_id] = sg_sum;

}

workgroupBarrier();

// scan subgroup sums (serial, small)

let num_sg = (WG_SIZE + sg_size - 1u) / sg_size;

if (lid.x == 0u) {

var sg_sum_total = 0u;

for (var i = 0u; i < num_sg; i = i + 1u) {

let tmp = local_data[i];

local_data[i] = sg_sum_total;

sg_sum_total = sg_sum_total + tmp;

}

let n_blocks = arrayLength(&block_sum);

if (wg_linear < n_blocks) {

block_sum[wg_linear] = sg_sum_total;

}

}

workgroupBarrier();

// add subgroup offset + intra-subgroup prefix

if (in_range) {

global_data[global_idx] = local_data[sg_id] + sg_prefix;

}

}Benchmark

Finally the GPU wins!

Some notes

- If you only need scan as a standalone operation, subgroups can be a big win. But if you want to fuse scan with other computations, a Blelloch-style approach may still be useful as a base. (Maybe?)

- There are even faster scan variants like Decoupled Look-back.

- My benchmark measures from submit until the device becomes usable again, so it does not include overheads of creating pipelines, bindgroups, etc. Thus for small , GPU scan is often not worth it.

- Blocked scans are basically mandatory for performance and for handling large arrays, but recursive intermediate buffers increase memory usage. I suspect there are smarter ways to manage that, which I didn’t dig further.

- WebGPU is fun🙂